Pittsburgh again receives ‘F’ for air quality in American Lung Association annual report

Hanna Webster / Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Pittsburgh has received a failing grade in the American Lung Association’s annual air quality report. Again.

Grading cities on particle and ozone pollution, the organization released the 26th annual State of the Air Report on Wednesday.

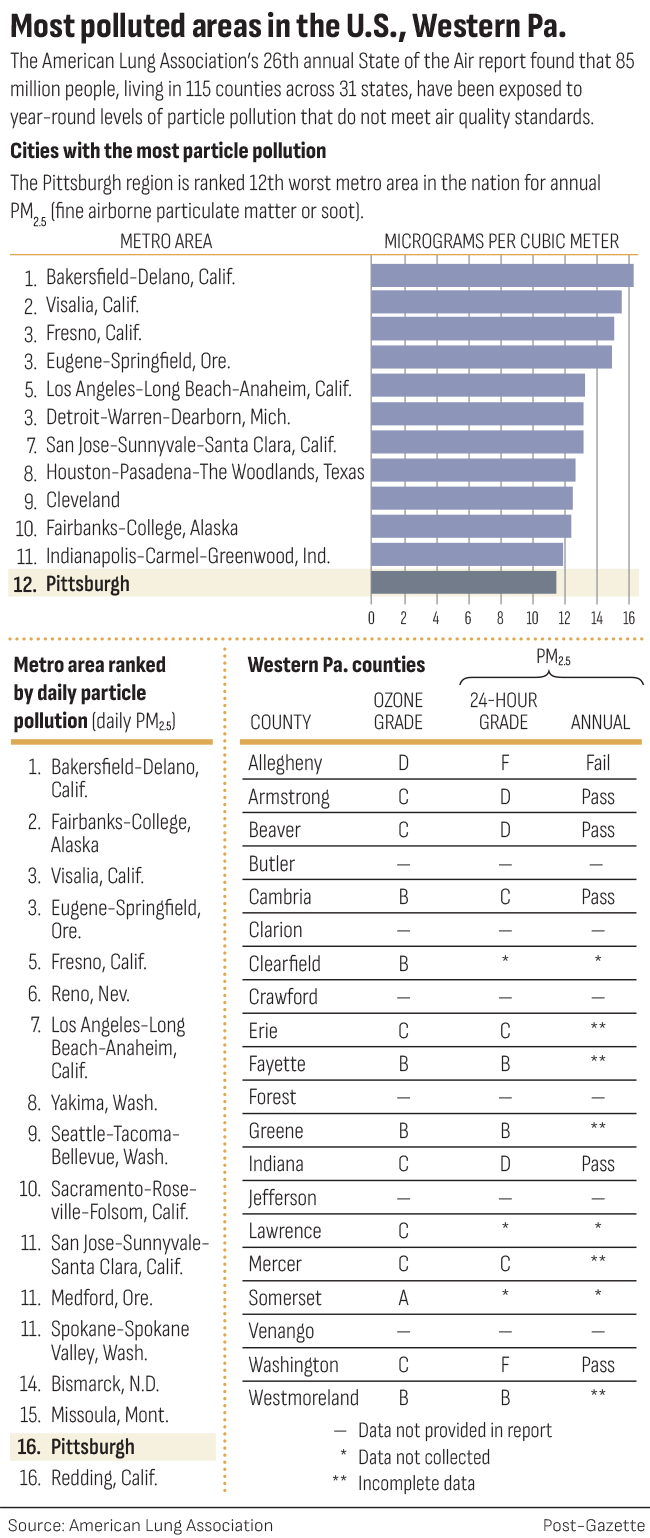

The Pittsburgh-Weirton-Steubenville area ranked 12th among the 25 worst cities for year-round particle pollution, and 16th for cities most polluted by ozone.

“This is not a good grade to take home to your mother,” said Kevin Stewart, director of environmental health at the American Lung Association. “We know one bad air day can be one too many for someone in a sensitive risk group who can have health responses as a result.”

Using 2023 data, the rankings come as the Environmental Protection Agency faces staff cuts and the Trump Administration intends to roll back air quality regulations. A series of January executive orders aims “to unleash America’s affordable and reliable energy and natural resources.”

Allegheny County has reckoned with its air quality for decades, as a historic steel producer that once had many more days considered “very unhealthy” and “hazardous,” compared to now, by the EPA, which consistently began measuring the air quality index and various particle pollutants in 1980.

Poor air quality, particularly fine particulate matter at 2.5 micrometers (PM 2.5), which can lodge deep into the lungs, has been associated with exacerbating respiratory conditions, including increasing rates of asthma, emphysema and chronic bronchitis, as well as cancer and heart disease. Premature death and low birth weight have also been linked to long-term exposure to air pollution.

In the U.S., air pollution has been attributed to 100,000 to 200,000 deaths each year, according to a 2020 analysis published with the American Chemical Society.

Air quality has, however, improved over time, both at the national and local level.

The 1970 passing of the Clean Air Act established regulations for major polluters, including the creation of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which caps the level of pollution, in micrograms per cubic meter, allowed for a given day and year. This has been reviewed and amended many times.

The Biden Administration lowered that cap from 12 micrograms per cubic meter to 9 in February 2024. The Trump Administration has announced its intentions to reconsider that cap.

“Under President Trump, we will ensure air quality standards for particulate matter are protective of human health and the environment while we unleash the Golden Age of American prosperity,” EPA Administrator Zeldin said in a March 12 statement regarding small particulate regulations.

Between 2010 and 2022, the number of tons of hazardous air pollutants emitted in Allegheny County dropped by 65%, according to the county’s Air Quality Dashboard.

The American Lung Association’s report credits the Clean Air Act for progress across the U.S.

“Since the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970, the combined emissions of six key air pollutants have fallen by 78%, according to EPA,” the American Lung Association report stated. “But as ‘State of the Air’ 2025 shows, many millions of people in this country are still breathing unhealthy air.”

People of color, those living in poverty, children and people with chronic health conditions fare the worst health effects from poor air quality. A 2020 analysis by local researchers published in the Journal of Asthma found that children with schools near pollution sites were more likely to be diagnosed with asthma.

Karen Clay, professor of economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University, specializing in air pollution, said the results of the American Lung Association report were not surprising, especially given Pittsburgh’s fraught industrial history.

“Pittsburgh, more than many places, has nontrivial industrial air pollution,” she said. “Unfortunately, it’s been a long-running political issue.”

It’s something the county health department has attempted to address, many times suing some of the largest polluters for breaking these regulations.

But in the current political climate, there may be fewer resources — and less support from the federal government — for local and state health departments to apply the same pressure they have in past years, said Ms. Clay.

“The problem is that a lot of the economic impact at the federal, state and local level hasn’t hit yet, and that will make it tricky for Allegheny County Health Department to find the resources to be putting a huge amount of pressure on industry,” she said.

Ronnie Das, ACHD spokesperson, said in an email that its Air Quality Program has worked diligently to strengthen enforcement, ensure compliance and update infrastructure to meet environmental regulations, and that its air monitoring network is “among the most comprehensive in the nation,” with nine “strategically placed sites” scattered across the county.

Allegheny County met all National Ambient Air Quality Standards in 2023, marking the third consecutive year of achieving those standards, he said.

Mr. Das said that while there were moments when pollution levels exceeded regulatory caps for ozone and hydrogen sulfide, context is important, “including the outsized impact of Canadian wildfire smoke and climate-driven events beyond our control.”

Some air quality experts interviewed took issue with the way the American Lung Association analyzed air quality data, saying it frames Pittsburgh as being in a worse position without looking at the greater context.

The American Lung Association pulls a county’s highest air monitor reading for the analysis, which, said Peter Adams, department head of engineering and public policy and an air pollution expert at Carnegie Mellon University, is not representative of the quality of the air most county residents are breathing.

Mr. Adams also questioned the ranking of cities for their air pollution altogether — as particle pollutants don’t ascribe to city, county or state boundaries.

“PM 2.5 really travels a long distance, hundreds or thousands of miles,” he said. “The idea that PM 2.5 is a city problem is inconsistent with the science. The entire northeast sort of sits in the same soup of pollution. This is very much a regional problem and not a city problem.

“I have strong misgivings about ALA ranking cities for air pollution, and I think that their methodology unfairly penalizes Pittsburgh,” said Mr. Adams in additional written comments to the Post-Gazette. “Our ranking is based on an air quality monitor in the immediate vicinity of the Clairton Coke Works. Most city and county residents are breathing air that is considerably cleaner than what the ALA uses in its rankings.”

A look at Allegheny County Health Department’s 2023 Annual Air Quality Report found that, among the county’s eight monitors, the average measurement between 2021 and 2023 was 9.1 micrograms per cubic meter, with half the monitors measuring under the new cap of 9 micrograms per cubic meter.

ACHD’s 2023 Air Quality Report also showed that, in the past two decades, nearly every monitor’s average reading has dropped by about half.

Mr. Das said that while ACHD “respectfully acknowledges the American Lung Association’s continued advocacy for clean air and their recent assessment of Allegheny County's air quality,” it believes the report’s conclusion doesn’t fully reflect the region’s progress, “nor the robust systems in place to protect the health and well-being of the more than 1.2 million residents who call Allegheny County home.”

Another issue: Air quality isn’t improving in a uniform way. Worsening wildfires — as seen throughout Canada in summer 2023 and in Los Angeles in January — record high temperatures and continued pollution from transportation are all stymying efforts to wrangle in the worst pollutants.

The American Lung Association report showed that the number of unhealthy air quality days, defined by the air quality index, have been increasing sharply since 2018. Allegheny County saw “unhealthy” and “very unhealthy” PM 2.5 readings in late June 2023, likely from the wildfire smoke wafting in from Canada, as well as a smattering of days throughout 2024 considered “unhealthy for sensitive groups” because of the pollutant ozone.

Rolling back the 9 ug/m3 cap to 12 could cost 4,500 lives per year, according to one EPA analysis.

“PM2.5 pollution is associated with tens or thousands of premature deaths in the U.S. per year, and the current administration wants to walk back that progress,” Mr. Adams said. “I think that’s irresponsible, dangerous and unlawful.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the distance PM 2.5 particles can travel. It is hundreds or thousands of miles.