PG investigation: Dark money floods key races in battleground Pennsylvania

By Mike Wereschagin and Jimmy Cloutier / Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

On a tree-lined street in Washington, D.C., tucked between a whiskey bar and a Tarot card reader’s shop, is a UPS store with a bank of small mailboxes set into the wall.

Along the bottom row in the far left corner is box 143. On paper, this inconspicuous mail drop just a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol is the conduit for tens of millions of dollars in untraceable money that has flooded into elections across the country this year.

The dollars have poured in Pennsylvania, where wealthy donors to both parties have shielded themselves from the public with the help of a small group of campaign law experts — middlemen enabling a surge of dark money into American politics.

Virtually unknown outside the world of campaign operatives and politicians, these firms have for years played a critical role in moving money that can’t be traced back to their donors but help shape the most important races in the nation.

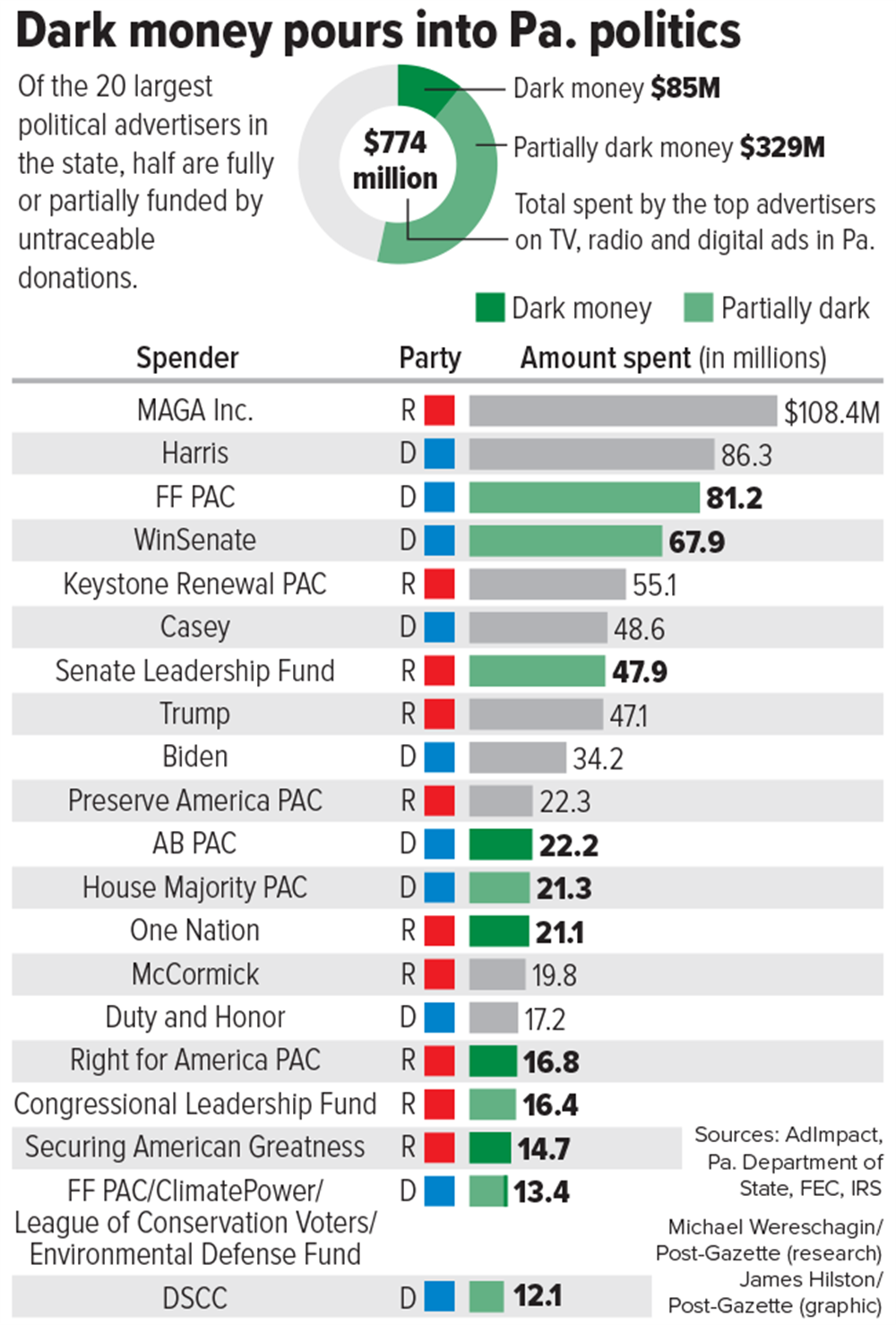

An analysis by the Post-Gazette found that more than $85 million in dark money has flooded directly into the state through groups that are formed for the sole purpose of preventing the public from knowing who is behind the contributions.

At a time when most Americans consider transparency a fundamental safeguard of elections, the amount of anonymous money moving into the state exposes a loophole in campaign finance rules that makes it more difficult for voters to know who is funding tens of millions in campaign ads.

“It seems like it just keeps going up,” said Saurav Ghosh, director of federal campaign finance reform at the Campaign Legal Center in Washington.

“The mere fact that [dark money groups] are permitted to spend the way they do on elections without any transparency – that's the real problem here,” Mr. Ghosh said. “But certainly the people —the humans — make that problem happen.”

Consider the mailbox at the UPS store near Capitol Hill. Box 143 is the address of Future Forward USA Action, one of the largest dark money groups supporting Democratic candidates this election cycle.

In late July, a little over a week after President Joe Biden dropped out of the race and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris, the group gave $20 million to FF PAC — which is listed at the same mailbox.

The super PAC is one of the largest spenders in Pennsylvania, funneling more than $80 million into the state to buy television, radio and digital ads to boost Ms. Harris’ campaign, according to AdImpact, a political ad-tracking firm.

In one of the PAC’s ads, the campaign rips former President Donald Trump, saying he’s “giving the middle finger to the middle class.”

The political committee is one of more than 110 with the same PO box and tied to the same campaign compliance firm: MBA Consulting Group, one of the small number of firms that set up the political committees and advise them on how to avoid the scrutiny of regulators.

Across the Potomac River, in Alexandria, Va.’s, historic Old Town, a colonial-style building houses a similar firm that caters to Republican-aligned groups.

Huckaby Davis Lisker — well known in GOP circles — helps run more than 240 political committees from its Washington Street address, including the leadership PAC of House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La.

Last year, one of the groups in the firm’s portfolio funneled almost $1 million into the race for Allegheny County executive — all of it in untraceable money.

Another super PAC run from the 1800s-era townhome has moved more than $22 million into the state to pay for ads that attack Ms. Harris as “weak” and “dangerous.”

“She created the worst border crisis in American history,” the narrator says in an ad that flashed across television screens in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Johnstown.

For transparency advocates, such firms are a familiar sight.

Recognized as experts in campaign laws, they will frequently set up nonprofits — social welfare organizations under section 501(c)(4) of the tax code — which allow them to take in unlimited amounts of money from donors without divulging their names.

Though barred from giving the money directly to candidates, the groups can buy ads that push a particular issue benefiting those candidates or funnel contributions to super PACs.

Dark money groups supporting Trump often focus on immigrants as a threat to the nation without ever mentioning the former president’s name.

As long as they spend more than half their money on so-called issue ads, the nonprofits can then use the rest to directly attack or support the candidate of their choice.

The ads push the same message, but the language is just different enough to slip through a legal loophole.

“There are all sorts of ways that lawyers and accountants help these groups get around the limitations placed on nonprofits,” said Robert Maguire of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a government watchdog group in Washington, D.C.

Making it even more difficult to track, the nonprofits can be created one day and be flush with millions of dollars the next.

From there, the money can pour into a super PAC — or be funneled directly into ad buys that blanket the airwaves of key states like Pennsylvania.

From May through mid-October, one dark money group backing the Trump campaign poured $14 million into ads in every media market in the state. During just the last three months, a similar group backing Ms. Harris plunked down more than $5 million in ads about the consequences of abortion bans on women’s health care.

The amount of dark money has surged in recent presidential elections. In 2012, it was $359 million, according to the nonpartisan research group OpenSecrets.

Then, in 2020, that figure shot up to more than $734 million.

So far in this election cycle, the researchers tracked $473 million, and spending is only expected to ramp up in the frantic final weeks of pivotal campaigns across the country.

Not long ago, this flood of untraceable money would’ve been illegal. That changed in 2010, when the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision known as Citizens United reshaped the political landscape by allowing corporations and outside groups to spend unlimited amounts to influence campaigns.

“In the years following Citizens United, you began to see just an explosion in the number of politically active nonprofits,” said Brendan Fischer, a Washington, D.C., lawyer and campaign finance expert.

Even then, the ruling raised fears that it would give wealthy donors unprecedented influence in politics — and possibly pave the way for foreign money to pour into American elections, in violation of U.S. law.

Just days after the court’s conservative majority handed down its ruling, then-President Barack Obama criticized the decision in his State of the Union address.

“Last week, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests — including foreign corporations — to spend without limit in our elections,” Mr. Obama said.

Sitting in the well of the House, Justice Samuel Alito, a key vote in the court’s majority, shook his head and, with an angry expression, mouthed, “Not true.”

At first, the Internal Revenue Service tried to police this new frontier the court had created. But as it began investigating the political nonprofits that had burst onto the scene — most of which, at the time, supported Republicans — it “triggered a right-wing backlash,” Mr. Fischer said.

“A number of right-wing groups and folks who would later become notorious, like Cleta Mitchell [a key figure in the 2020 election-denial movement], began to claim that the IRS was engaging in unfair targeting of political voices, trying to suppress the speech of conservatives,” he said.

“Eventually, the IRS backed down and decided that, ‘We're just not going to play here,’” Mr. Fischer said.

At the same time, the Federal Election Commission — an agency created after the Watergate scandal to monitor campaign spending — became paralyzed by its political appointees.

The agency needs a majority of its six-member board to agree to take enforcement actions, but the three Republican appointees often deadlock with their three Democratic counterparts, leaving investigations into campaign finance violations to languish.

The result, experts say, is that the two agencies most responsible for policing money in politics rarely take action against dark money groups.

“Right now, we have to take politically active nonprofits at their word that they are not using foreign money to influence elections, but the honor system leaves a lot to be desired,” said Michael Beckel, research director of Issue One, a good-government advocacy group based in Washington, D.C.

Despite Justice Alito’s public denial that foreign money would creep into campaigns because of the high court’s ruling, regulators found that it was indeed happening.

In 2018, a Canadian steel magnate played a key role in steering $1.75 million to a pro-Trump super PAC, according to the FEC. The executive, Barry Zekelman, was fined $975,000.

In 2022, two associates of former Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani — Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman — were sentenced to prison for funneling money from a Russian businessman into the U.S. political system.

One reason that supporters of candidates turn to campaign firms in Washington and elsewhere is to sidestep the scrutiny of regulators.

“If you have enough money to spend millions of dollars in elections, you have enough money to hire the best lawyers and accountants in the country to cover your tracks,” Mr. Maguire said.

The question of how much campaign treasurers should know about the money they collect briefly became the focus of a rare FEC investigation into a dark money group in 2023.

The FEC was responding to a complaint by Mr. Maguire’s group, CREW, that raised questions about whether the dark money entity was illegally routing donations to a PAC through a nonprofit to hide the true donor.

The PAC’s treasurer, Lisa Lisker, of the Alexandria firm Huckaby Davis Lisker, told investigators that she didn’t know where the nonprofit had gotten the money that it donated to her committee.

After a two-year investigation, the FEC commissioners deadlocked, 3-3, over whether the corporations that were funding the PAC broke the law. They voted, 4-2, that Ms. Lisker didn’t knowingly accept illegal contributions to the PAC.

That same year, Ms. Lisker also would serve as treasurer for a committee that moved nearly $1 million in dark money into the Allegheny County executive race.

The money was then used to pay for a barrage of ads on behalf of Republican Joe Rockey, including attacks on his Democratic opponent, Sara Innamorato. The dark money group would go on to outspend Ms. Innamorato two to one in broadcast ads.

She would eventually prevail, but by less than 3% in the closest race for that office in decades. Ms. Lisker declined to comment. MBA Consulting did not respond to interview requests.

While the Citizens United case paved the way for dark money in the elections system, it also unleashed massive amounts of money from rich donors with virtually no limits.

Just last month, Elon Musk contributed $30 million to his own America PAC in a single donation — bringing his total to $75 million.

Since the Citizens United case, Democrats have tried to roll back the court’s decision through legislation like the DISCLOSE Act, a bill that would impose new requirements on political groups to report the true source of their donations.

The bill has been introduced in every term of Congress since the 2010 ruling but has been blocked by Republican opposition in the Senate.

But even as the Democratic Party has pushed for tighter restrictions on anonymous donations, supporters have moved swiftly to open new pipelines for the flow of dark money into campaigns.

In every election cycle since 2018, Democratic dark money groups have outspent their Republican counterparts, according to OpenSecrets.

“What we've seen time and time again is that when one side identifies a loophole, the other side is going to follow suit and exploit it,” Mr. Fischer said.

With 16 days still to go, and the state positioned to play a decisive role in control of the White House and possibly Congress as well, the flood of untraceable money is expected to continue.

"With the stakes of the presidential race and the stakes of the Senate race and House campaigns, voters are being deluged by dark money in Pennsylvania," Mr. Beckel said.

Deputy Managing Editor for Investigations Michael D. Sallah contributed to this report.