Pittsburgh, city of pickles, marks a decade of Picklesburgh and the history that spawned it

Mia Rose Kohn / Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The goal was simple: a giant, inflatable pickle.

In 2015, Jeremy Waldrup, president and CEO of the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, presented a plan to his executive committee: “We want to do this specialty food festival. We’re going to call it Picklesburgh, and I’d like to spend a lot of money on a giant, inflatable pickle,” he said.

“They kind of looked at us like we were crazy.”

But that pickle took to the skies later that year, with 22,000 visitors attending the inaugural Pickleburgh, a multi-way festival that has since grown to 250,000-some attendees.

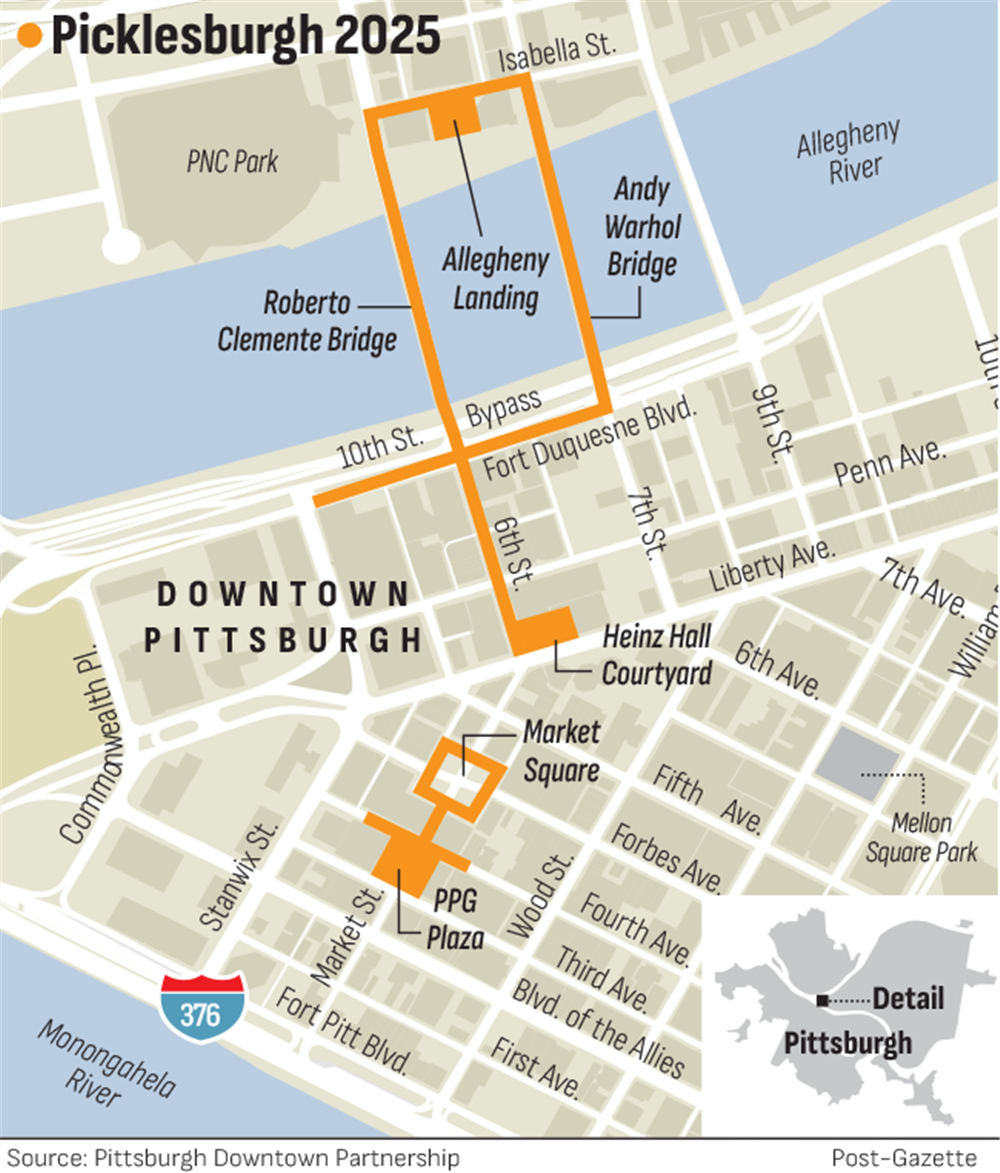

Picklesburgh has become part of Downtown’s economic development strategy, said Waldrup. Beginning Friday and running through Sunday, the festival, partnering with 23 restaurants and retailers based in the city center, returns with its largest footprint yet — including taking over two Downtown bridges.

“Our hope is that patrons fall in love with one of our restaurants and can’t wait to come back, or they see that Heinz Hall is absolutely beautiful and decide to come back for a show,” Waldrup said.

Fifty-four total vendors will set up for this installment, including some originals.

“We've done this for 10 years, and it’s always excitement and anxiety at the same time,” said Greg Andrews of The Pickled Chef, who has been at every iteration of Picklesburgh since its debut.

In July 2015, when Andrews’ son, August, was just 3 months old — small enough to strap into a BabyBjörn, as The Pickled Chef set up shop on the Rachel Carson Bridge.

Selling hand-packed, artisanal dill pickles relish, tomato jam and apple bourbon jam in addition to signature grilled cheese sandwiches –– options include relish, kimchi (the “kimcheese”), and a salami with homemade herb green mustard –– The Pickled Chef sold 1300 jars and 700 sandwiches and 1300 jars in two days.

By day two, The Pickled Chef was out bread and cheese and, Andrews said, he was scrambling through Downtown bakeries to locate loaves. The Restaurant Depot in the Strip District replenished his supply of cheddar cheese.

“We didn’t know what we were getting into,” said Andrews, who had begun selling his small-batch, farm-to-table products just one year prior.

Pickled history

Though Waldrup’s pitch ended with that gargantuan gherkin flying high, his vision began with something more grounded: summertime slumber.

“We were talking about July in Downtown Pittsburgh –– it can sometimes be a little quiet,” said Waldrup, thinking back to early 2015. “If the Convention Center is dark for a weekend, if the Pirates are out of town, you can kind of be alone.”

He and his colleagues were spitballing in their Downtown offices when Russell Howard, then-vice president of special events and development, chimed in.

“He was like, ‘You know, we should think about pickles,’” recalled Waldrup.

Pickles had it all: culinary potential, local cultural heritage with the legacy of H.J. Heinz and a global appeal that transcends any one culture. Plus, maybe the theme could get buy-in from the budding farm-to-table movement, Waldrup thought.

He credits Leigh Frank, a vice president of marketing with the Downtown Partnership, for the Picklesburgh name. And everyone got to work, including Howard, who researched Macy’s Day Parade floats.

The city gave its blessing, as did The Heinz Company; Allegheny County followed, with permission to host the inaugural festival on the Rachel Carson Bridge.

In July 2015, 25 vendors sold across two days of Picklesburgh.

“I don’t think there was a pickle left in Southwestern Pennsylvania that weekend,” said Waldrup. “We knew we were on to something.”

Enter social media platform TikTok, and several viral posts about the festival in early 2019 — some with nearly two million views, said Waldrup –– and that year, visitor counts doubled, reaching 44,000. That same year, Picklesburgh was named by USA Today readers as the #1 Best Specialty Food Festival in the country for the first of four times, most recently in 2024.

Attendance climbed from there: 50,000 visitors in 2021, 73,000 in 2022, 200,000 in 2023 and 250,000 in 2024 –– nearly 80% of the city's population of 307,668 per the U.S. Census Bureau.

In the 10 years since the giant pickle was first inflated –– save for 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the festival and the giant pickle popped during an attempt to turn it on its side –– Picklesburgh has inhabited every one of the Three Sisters bridges, and grown to as many as four days long.

The roster of events has grown over the years to include competitions — for pickle juice drinking, pickle bobbing and pickle eating — in addition to performances from local musicians. New this year, attendees can ride a mechanical pickle (think: bull-riding).

And Pittsburgh-based businesses, including Turner’s Ice Tea and Pittsburgh Brewing Co., release annual pickle editions of their beverages

“This event is no longer a street festival. It’s a Downtown celebration,” said Waldrup. “It’s about this only-in-Pittsburgh moment. It’s quirky. It’s silly. We want people to be like, ‘What in the world are they gonna think of next, and why do I need a pickle beer in my life?’”

Waldrup expects up to 260,000 visitors this year, but is "prepared for more,” with the event being held for the first time across two bridges as well as as well as Allegheny Landing, Fort Duquesne Boulevard, PPG Plaza, Market Square, 6th Street and Heinz Hall Garden

“It’s not just the cucumber,” said Waldrup. “We want people to smile and get a little silly with us and embrace this quirky culture that we have created here in Pittsburgh for a couple of generations now.”

A decade’s worth of Picklesburghs

How do you measure a life? For The Pickled Chef, it’s done in Picklesburghs.

Just as Greg Andrews and wife Ashlee Andrews of The Picked Chef have returned yearly, so has their son August, now 10. August will return this weekend along with sister Audra, 7, and their maternal grandmother, Debra Driggers, who rounds out The Pickled Chef’s team.

Another tradition continues: The family will, as they have since 2015, pose in front of the giant inflatable pickle for their annual family photo.

After a decade, the Andrews have their Picklesburgh routine down.

At the 2016 festival, The Pickled Chef sold 1,100 sandwiches; by 2023, that total jumped to 4,600 over 26 hours of service, with an average of one sandwich made every 21 seconds. The number again grew, to 5,700 sandwiches in 2024.

Prep starts about a month before game day, with peeling, dicing and crushing pickles and apples for the 40 gallons of dill pickle relish and 20 gallons of apple jam Greg Andrews plans to sell. He also brews the brine and hand-trims cucumbers for his seven varieties of pickles.

Then there are 900 to 1,000 pounds of cheese to take care of –– a precise melange of cheddar sourced from Pleasant Lane Farms, located near the Pickled Chef’s kitchen in Latrobe, mixed with commercial cheddar. (The local stuff has too little moisture content to achieve a satisfying stringiness when melted, Andrews explained.)

His bread, which he developed with a Shop N Save branch he passes on his way to work from his home in Greensburg, is a composite too: part polish potato bread for crispiness, part sourdough for tang. He’ll go through 700 loaves, plus five 36-pound cases of butter.

Even though Andrews isn’t actually much of a pickle fan –– it’s his family who clamors for the cured cucumbers –– the hassle is worth it for his pickles, he said.

“We take a lot of pride in our product. It's a little bit spicy, it's got a good salt content and then a nice sour dill at the end,” he said. “We have people that say it takes them back to their childhood, or it reminds them of a kosher dill from a Jewish deli.”

City of pickles

Though the festival debuted a decade ago, pickles have a much longer claim to the city’s history.

“We really could be called Picklesburgh as well as the Steel City,” said Andy Masich, president and CEO of the Heinz History Center. “Before ketchup was a gleam in H. J. Heinz's eye, he was making money with pickles. That was really his first big product.”

In 1855, a 10-year-old Heinz began selling pickled radishes from his mother’s garden in Sharpsburg, eventually planting his own vegetable garden.

More than three decades later, in 1889, he won a first place medal in the agriculture category of the Paris Exposition, where the Eiffel tower was unveiled.

Back in the U.S., much to Heinz’s disappointment, he was placed on the second floor of the agriculture building at the Columbian Exposition world's fair in Chicago, 100 steps above the gallery below. Without elevators or escalators, few patrons bothered to make the trek.

Heinz decided to print gold-colored tags, which young boys sprinkled on patrons below, said Masich.

“Men and women, arm-in-arm, would be strolling by and catch a glint of gold from the corner of their eye,” said Masich. The tags would instruct visitors to climb upstairs to collect a free prize: the now-famous Heinz pickle pin.

“They went up the stairs by the hundred of thousands, nearly a million people –– so many people crowding, that the floor began to buckle,” Masich said. “They had to reinforce the floor with posts.”

Heinz gave away more than a million one-and-a-quarter-inch-long pins with a green Heinz-branded pickle. One New York magazine wrote, “A Pittsburgh entrepreneur who found himself in a pickle, was saved by one,” said Masich.

The pickle became Heinz's favorite marketing material.

“To this day,” said Masich, “any true Pittsburgher has a pickle pin in their jewelry box or someplace in their house, whether they picked it up as a kid on a school field trip to the Heinz plant or somewhere along the line here at the Heinz History Center.”

On display in the Strip District museum is a 170-year-old jar of pickles –– the oldest in the world –– found 45 feet under a corn field in Kansas City. The jar sank aboard a Pittsburgh-built steamboat that collided with a sunken tree branch in the Missouri river in 1865. The river slowly changed course, leaving the pickles, still green, below the corn fields. When the pickles were found 150 years later in 1989 –– exactly 100 years from when Heinz won his gold medal in Paris –– they were edible.

“One of the diggers actually pulled the cork out of the top of the jar, reached in and ate one of the pickles and didn't die,” said Masich, “and in Pittsburgh, we count that as edible.”

Patrons can buy pickled-flavored lip balm and class pickle Christmas ornaments from the Heinz History Center –– or at the museum’s pop-up booth at Picklesburgh this weekend. They’ll be stationed on the Roberto Clemente Bridge, near the floating pickle.

“People still love pickles,” said Masich. “There’s something about a dill pickle that just hits the palette just right.”

Hours are noon-10 p.m. Friday and Saturday and noon-6 p.m. Sunday. More details at picklesburgh.com.

Correction, posted July 10, 2025: An earlier version of this article misstated who researched parade floats for the inflatable pickle. It was Russell Howard. In addition, the name of the Chicago world’s fair was incorrect; it was known as the Columbian Exposition.